THE AGA KHAN

by Peter Mansbridge

A portrait of Peter Mansbridge of CBC Canada. Photo Credit: Photo by Dustin Rabin.com, Toronto – July 25, 2007. Copyright: Dustin Rabin.

Editor’s Note: The following interview has been excerpted from Peter Mansbridge One on One by Peter Mansbridge. Copyright © 2009 Peter Mansbridge. Interview Material © Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Reprinted by permission of Random House Canada.

The Story Behind the Interview

There are about eighty thousand Ismaili Canadians in our country, and when I decided to interview their spiritual leader, the Aga Khan, his Canadian representatives told me that every single one of them would be watching. They weren’t kidding. Every time I meet an Ismaili Canadian, whether in Edmonton, Calgary, Toronto, Ottawa or any of the other urban areas they seem to favour, I’m stopped and told how great the interview was. One on One airs at least three times every weekend on the CBC, and one of those airings is in the middle of the night.

The audiences at that time are understandably small – often no more than fifteen thousand. So I had to smile when I saw the overnight ratings the first time the Aga Khan’s interview ran: eighty thousand.

Ismailis are a minority in the Muslim faith; in fact, some Muslims don’t even recognize them as Muslims. Their history is deep, ancient and to a degree bitter. Ismailis broke away from the main Shiite Muslim faith about twelve hundred years ago over who best represented the true Imam, or leader of Islam. I’ve seen some Ismaili friends at work shunned by other Muslims, who refused to accept them as friends and barely acknowledged them

as colleagues.

as colleagues.

His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan is the leader of the world’s Ismaili community, and he has spent many of his fifty years as the Aga Khan trying to counter those differences. He’s become a well-known and well respected international figure and his admirers exist far beyond his faith. He established the Aga Khan Foundation to improve living conditions and opportunities for the poor, whatever their faith, origin or gender. He was a great friend of Pierre Trudeau; his trips to this country during the Trudeau years were frequent and they continue that way now.

While the Trudeau relationship became broader in scope, it was based on the former prime minister’s decision in the early seventies to admit to Canada thousands of Asians who had been expelled from Uganda by the brutal dictator Idi Amin. Many of the new arrivals were Ismaili, and they, and the Aga Khan, have never forgotten Canada’s open doors in their time of need.

All of those points had made me determined to invite the Aga Khan onto One on One during one of his frequent Canadian visits. The opportunity came in early 2007.

When I flew to Ottawa for the interview, I took with me a good friend and colleague. Sherali Najak is the executive producer of Hockey Night in Canada, and years ago he worked with us on The National. He’d begged me and my regular director, Fred Parker, to let him direct the Aga Khan shoot. Freddie, normally very protective of his turf, said, “Absolutely,” and so did I. Sherali, you see, is Ismaili. His family story traces back to those Uganda days, and for him this opportunity to be in the same room as the Aga Khan was going to be a life-defining moment.

The interview was enjoyable and informative. The Aga Khan is a moderate Muslim leader at a time when many Muslims and Christians are wondering if they will ever get along. His thoughts on that topic were provocative, but we started by trying to understand his fondness for Canada.

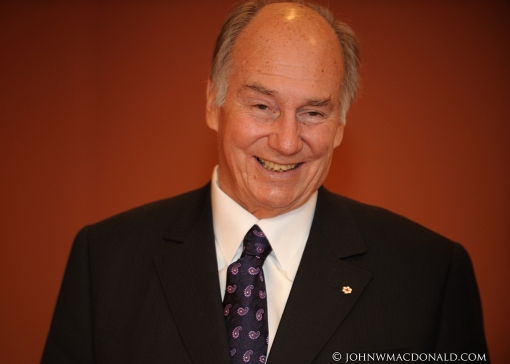

His Highness the Aga Khan, 49th Ismaili Imam and direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad pictured at Rideau Hall on October 7, 2010, where he was received by Canada’s 28th Governor General, His Excellency David Johnston. Photo: John MacDonald, Ottawa. Copyright.

Peter Mansbridge: You must love Canada – you keep coming back here.

Aga Khan: I do.

PM: What is the quality that you most admire about this country?

AK: I think a number of qualities. First of all, it’s a pluralist society that has invested in building pluralism, where communities from all different backgrounds and faiths are happy. It’s a modern country that deals with modern issues, not running away from the tough ones. And a global commitment to values, to Canadian values, which I think are very important.

PM: Let’s talk about that a little bit, because I wonder whether your confidence in Canada has in any way been shattered a little bit in these past few years, especially since 9/11. There have been tensions in this country, as there have been in many other Western countries, between Muslim and non-Muslim societies – on any number of levels, on both sides, about history, religion, tradition and integration within society. How much has that concerned

you?

you?

AK: It concerns me and at the same time it doesn’t, in the sense that, to me, building and sustaining a pluralist society is always going to be a work in progress. It doesn’t have a finite end. And so long as there is national intent, civic intent to make pluralism work, then one accepts that it’s a work in progress.

PM: Let me go a little deeper on that, because it raises a question you have often raised, and that’s the issue of ignorance. You reject the theory of a clash of civilizations, or even a clash of religions. You believe there’s a clash of ignorance here, on both sides of that divide. And you’ve felt that way for a long time. I was looking through the transcripts of an interview you gave in the 1980s in Canada where you were warning the West that it had to do a better job in trying to understand Islam. That clearly hasn’t happened.

AK: No, it hasn’t happened. A number of friends and people in important places have tried to contribute to solving that problem, but it’s a long-established problem. It’s going to take, I think, several decades before we reach a situation where the definition of an educated person includes basic understanding of the Islamic world. That hasn’t been the case. And the absence of that basic education has caused all sorts of misunderstandings.

PM: What’s been the resistance?

AK: I think it’s essentially historic. I think that Judeo-Christian societies have developed their own education, and basic knowledge of the Islamic world has simply been absent. Look at what was required for an education in the humanities; for example, I was a student in the U.S. and education on the Islamic world was absent.

PM: Is this a one-sided clash of ignorance?

AK: No, I think there is ignorance on both sides, and I think very often there’s confusion. I think more and more there has been confusion between, for example, religion and civilization. And that’s introducing instability in the discussion, frankly. I would prefer to talk about ignorance of the civilizations of the Islamic world rather than ignorance just on the faith of Islam.

PM: What we’ve witnessed in the last couple of years, not just in this country but in other Western countries as well, is what we call “homegrown terror,” where you see young Muslim men – born in the West, educated in the West – moving towards a fundamentalist view, a militant view of Islam. Why is that happening?

AK: There is without any doubt a growing sense amongst Muslim communities around the world that there are forces at play that it doesn’t control, that views the Muslim world with, let’s say, unhappiness or more. I would simply say, however, that if you analyze the situation I don’t think you can conclude that all Muslims from all backgrounds are part of that phenomenon. Secondly, if you go back and look at the communities where this is common, you will find that there’s a long-standing unresolved political crisis in the community. It’s very, very risky, I think, to interpret these situations as being specific to the faith of Islam. It is specific to peoples, sometimes ethnic groups, but it’s not specific to the face of Islam.

PM: That must really concern you. Your followers see you as a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, the same prophet that some of these minority fundamentalist militant groups hold up and claim as the reason they’re doing the acts they’re doing.

AK: Again, I think one has to go back and say, “What is the cause of this situation?” With all due respect, if you look at the crisis in the Middle East, that crisis was born at the end of the First World War. The crisis in Kashmir was born through the liberation of the Indian continent. These are political issues originally; they’re not religious issues. You can’t attribute the faith of Islam to them. I think the second point I would make is this tendency to generalize Islam. There are many different interpretations of Islam. As a Muslim, if I said to you that I didn’t recognize the difference between a Greek Orthodox or a Russian Orthodox or a Protestant or a Catholic, I think you’d say to me, “But you don’t understand the Christian world.” Let me reverse that question.

PM: Canada’s role in Afghanistan is well-known, has been since 9/11. So is the Aga Khan Foundation, which is in there in a big way in development matters. The question is simple, really: with all the help that’s been given to Afghanistan, why is the Taliban resurging? Not only in numbers, but in popularity as well. Why is that happening?

AK: I think there are a number of reasons, but the one that I would put forward as the most immediate is the slow process of reconstruction.There was a lot of hope that once there was a regime change and a new government and the political process had been completed, the quality of life would change. It hasn’t changed quickly enough. It’s taken much more time than I think many of us had hoped to get to isolated communities in Afghanistan and improve their quality of life. It’s an organizational problem. Even amongst the donor countries there have been differences of opinion. The management of the drug problem has not been a united effort by any means. So there are a number of things that have slowed up the process. And there are still acute pockets of poverty in Afghanistan: people who don’t have enough food, people who don’t have access to any education, any health care. It is clear this sort of frustration causes bitterness and the search for other solutions.

PM: Is there time to turn it around? Because you get a sense that the pendulum has swung back considerably in the last year or so. There’s this growing sense of frustration among the Canadian people and a belief that it’s a war that cannot be won.

AK: I would beg to differ on that. I think what we’re seeing in Afghanistan, at least from my own network of activities, is an increasingly visible two-speed process, where in the north and the west you’re beginning to see quantifiable change. In the east and the south you’re not seeing that. Two-speed change is going to have to be managed with great care, but it’s not a good reason to give up by any means.

PM: Can you do both at the same time? That’s the debate in Canada: to run a military operation – talking specifically about the south – while trying to introduce aid and development in an area that is not secure.

AK: It’s very difficult to do, but necessary. Every step counts. Certainly in areas where there’s insecurity, I think the availability for populations to participate in these development activities does go down when quality of life changes. And I believe the same thing with regard to the drug problem.

PM: How much of the problem in Afghanistan is a result of the decision on the part of the Americans and the British to move into Iraq?

AK: Very substantial indeed. The invasion of Iraq was something which has mobilized what we call the Imamat – the community of Muslims around the world. Every Muslim that I have ever talked to has felt engaged by this.

PM: On what level?

AK: Baghdad is one of the great historic cities of the Islamic world. Iraq is not a new country; it’s part of the history of our civilization. It’s been a pluralist country and has produced great philosophers, great historians, great scientists. Reverse the question again. What would the Christian world think if a Muslim army attacked Rome? I think there would be a general reaction in the Christian world, not just an Italian reaction.

PM: But it seems that even in the Muslim world, that invasion has caused major divisions – the clash inside Islam itself, between Shia and Sunni.

AK: That was entirely predictable. Entirely predictable. What you are effectively doing is replacing a Sunni minority government in a country that has a Shia demographic majority. And again, what would happen – I’m sorry to come back to this, but it’s important – if a Muslim army went in to Northern Ireland and replaced one Christian interpretation by another? Imagine the fallout that that would cause in the Christian world itself.

PM: So what happens now? Can Iraq be put back together? And who would be doing the putting back together?

AK: I think that’s a very, very difficult question, and I would not want to predict the answer. Because I think that the whole process of change in Iraq has regional dimensions which have got to be managed. They’re not national dimensions in Iraq. Those regional dimensions also were predictable, let’s be quite frank about it. I think they’re going to need to be managed with very, very great care.

PM: Is the answer, as some suggest, the splitting of it into three regions with the main two combatants, the Shia and the Sunnis, actually separated by borders?

AK: That’s really, I think, an issue where the leaders of the three communities have got to agree or not. In my life, in the past fifty years, I have been uncomfortable with the creation of unviable states. So I would ask this question: if you did do that, what components of Iraq would be stable, viable states in the future?

PM: Who’s showing leadership in this world right now in terms of the major global issues? Who do you look to as a leader, whether it’s a political leader or not?

AK: I think there are a number of people in the U.N. system who’ve shown leadership, who have shown balanced judgment on these issues. Because when all is said and done, it’s the balance of the judgment that counts. And it’s understanding the issues. I think, amongst others, Kofi Annan has been remarkable in his understanding of the issues. He’s also had a team of people around him who are very good.

PM: It’s quite a condemnation though of the political leaders of our generation that you don’t point to one of them, no matter which side of the divide we talked about earlier. You don’t see one there?

AK: I’m looking at the regions of Africa, Central Asia, and I’m asking myself within this context who’s having the greatest influence. I think that certainly the U.N. Development Program…I think the World Bank and Jim Wolfensohn changed direction very significantly and dealt with real human issues and has done a wonderful job.

PM: Some people suggest that there’s been a movement in terms of real leadership away from governments to private foundations, philanthropic organizations – yours being one, the Gates Foundation, and you can name a number of them. Do you see that happening? Is that a good thing?

AK: I see it happening, and I welcome it wholeheartedly. Because what we’re talking about, I think, is accelerating the construction of a civil society. I personally think that civil society is one of the most urgent things to build around the world. Because one of the phenomena you see today is the number of countries where governments have been unstable. Progress is made where there’s been a strong civil society, and that’s a lesson that I think all of us have to learn. My own network is immensely committed to that. And so what the Gateses and others are doing is providing new resources, new thoughts to create civil society. Whether it’s in health care or education, it’s the combined input which is so exciting and so important.

PM: We touched briefly earlier on the new Global Centre for Pluralism, which will be established here in Canada through the Aga Khan Foundation and the people of Canada through the Government of Canada. What is your hope for that? What do you see that doing, accomplishing?

AK: I hope that the centre will learn from the Canadian history of pluralism, the bumpy road that all societies have in dealing with pluralist problems, the outcomes, and offer the world new thoughts, new ways of dealing with issues, anticipating the problems that can occur. Because in recent years I think we’re seeing more and more that no matter what the nature of the conflict, ultimately there is a rejection of pluralism as one of the components. Whether it’s tribalism, whether it’s conflict amongst ethnic groups, whether it’s conflict amongst religions, the failure to see value in pluralism is a terrible liability.

PM: Why Canada?

AK: Because I think Canada is a country that has invested in making this potential liability become an asset. I think that Canada has been perhaps too humble in its own appreciation of this global asset. It’s a global asset. Few countries, if any, have been as successful as Canada has, bumpy though the road is. As I said earlier, it’s always going to be an unfinished task.

PM: Next year is your golden jubilee: fifty years. What’s your – I was going to say what’s your dream for the world in that year, but I guess dreams are dreams. What’s your realistic hope?

AK: In areas of the world which are living in horrible poverty, I’d like to see that replaced by an environment where people can live in more hope than they’ve had. I’d like to see governments that produce enabling environments where society can function and grow rather than live in the dogmatisms that we’ve all lived through, and which I think have been very constraining. And I’d like to see solid institutional building, because, when all is said and done, societies need institutional capacity.

PM: Those are grand hopes. I’m sure they’re shared by many. How realistic do you think it is that we can achieve anything like that?

AK: I think we can achieve a lot of that. I think the time frame is what we don’t control. I remember in the mid-fifties reading about countries in the developing world being referred to as basket cases. Fifty years later those are some of the most powerful countries in the world – enormous populations. They’re exporting food when fifty years ago we were told they’d never be able to feed themselves. They had an incredible technology deficit fifty years ago. Today they’re exporting technology, homegrown technology. So I think there are a number of cases out there where we can say what we don’t control is the time factor. But society does have the capability to make those changes.

PM: So there is reason for hope.

AK: I believe so, God willing.

Postscript by Peter Mansbridge: As inspiring as his message was, the lasting memory I take from that day was more personal. It was the beaming face of Sherali Najak standing next to the Aga Khan for that special photograph he had so wanted to get. The man who regularly bosses Don Cherry around looked pretty tame all of a sudden.

Interview Material © Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Reprinted bySimerg permission of Random House Canada.