The following article is courtesy of the thefridaytimes.com

by Dr Sayed Amjad Hussain

Since time immemorial, humans have faced the challenge of physical, cultural, or psychological divides placed in their way. They have tried to overcome those obstacles by building bridges; physical as well as non-physical.

Bridges, as physical structures, span bodies of water, geological gaps and connect often disparate people and places. The word bridge has also entered the vocabulary as a metaphor that takes the concept of a bridge to a different level.

There are bridges of understanding between different cultures and religions. We build such bridges to know people who are not like us. Such bridges allow us to understand other people and appreciate their culture and language. In a shrinking world, otherwise called the global village, such bridges lead us to the proverbial Tower of Babel where we begin to understand and even appreciate the differences among us.

If we do not build the bridges of understanding, we will be isolated islands in a vast ocean surrounded by strange people, strange tongues and strange cultures. Isolation can lead to paranoia of others and in that state of mind we train our eyes and sometimes our weapons, in the direction of people we don’t know and don’t understand. Sir Isaac Newton had famously said that we build too many walls and not enough bridges.

In a way, physical bridges lead to the building of cultural and economic one’s. I witnessed that phenomenon during my travels and particularly during explorations of the Indus River in Tibet and Pakistan.

The Indus is one of the great rivers of the world. It arises in western Tibet and after traveling 2,000 miles through Tibet, Indian Kashmir, Pakistani Kashmir, and Pakistan it empties into the Arabian Sea near the southern Pakistani port of Karachi.

In the 1980s there were very few bridges spanning the Indus River. Most of the travel across the river was done by flat-bottom cargo boats. People on either side did not know much about the people on the other side.

The word spread and a Christian radio station asked the public to come to the Center to show solidarity with the local Muslims. More than two thousand people responded to the call. They made a double ring around the Center, holding hands and facing outwards in a symbolic gesture of protecting the Center

During Indus expeditions, I crossed the river many places along its long journey to the Arabian Sea. In the mountains, there are very few bridges and people cross the river by whatever means they could find. These included inflated goatskins, boats, or just swimming across to the other side. In the lower reaches of the river there were many pontoons or boat bridges. In other places, the steel and concrete spans have replaced the boat bridges. People crossing those bridges, either by foot, riding an animal or traveling in a vehicle are not isolated on one side anymore.

Bridges, whether physical or metaphorical, connect people and places. We build bridges because we have an innate urge to connect with others and in the process, we become more tolerant and more understanding of those who are not like us. We should celebrate those who build bridges.

And then there are people who burn bridges. Sooner or later, those people realize that they are stranded and often it is too late.

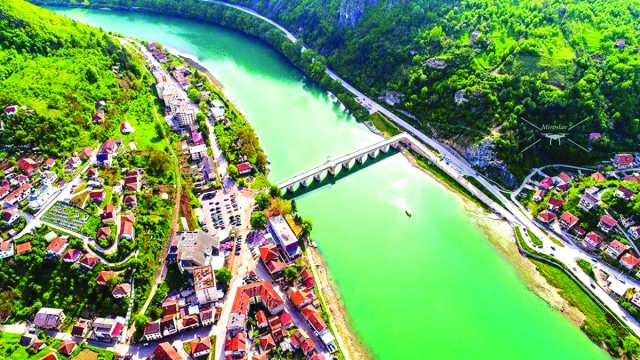

Perhaps no other span signifies deep religious and cultural divides than the 16th-century bridge over the Drina River in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The bridge divides the Serbs and Bosnians. The Los Angeles Times called it the Bridge of Disunity. It has been an age-old flash point between Christians and Muslims.

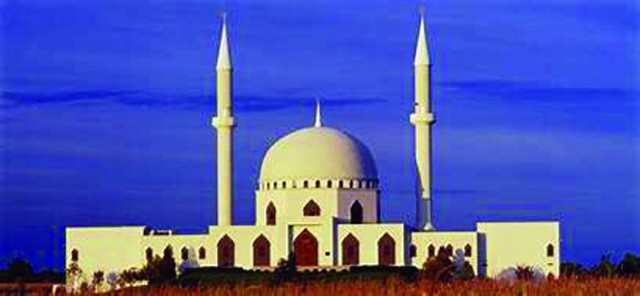

In the aftermath of the attack on the World Trade Center in New York and elsewhere in the US on September 11, 2001, there were vigilantes who went on rampage and killed Muslim and Muslim-looking men such as Sikhs. In our town, a sharpshooter trained his gun on the Islamic Center of Greater Toledo and emptied a round causing the stained glass windows to shatter. There were no fatalities or injuries. The Islamic Center has an iconic building that sits at the confluence of two major interstate highways.

The word spread and a Christian radio station asked the public to come to the Center to show solidarity with the local Muslims. More than two thousand people responded to the call. They made a double ring around the Center, holding hands and facing outwards in a symbolic gesture of protecting the Center.

The same spirit was observed in 2012, when a man steeped in the hatred of Islam, entered the Center, and lit a flame after pouring petrol on the mussala or the prayer area. The fire destroyed parts of the Center and made the building unusable because of water and smoke damage. It took 6 months and 1.5 million dollars to restore the Center.

In the aftermath of the incident, the civic and religious groups came together on the Center grounds and pledged solidarity with Muslims of Toledo. They all prayed for our safety. One can imagine the beautiful bridges of understanding and compassion that exist in some parts of the US.

I met Father Bacik over lunch a few weeks prior to the Dialogue to explore different themes that we could address. He said that traditionally the speakers turn the Dialogue into showcasing and boasting about their religion. He suggested that instead we consider looking inwardly and be critical of certain aspects of our religions

The police and FBI were vigilant and within 24 hours the arsonist was arrested at his home in the neighboring state of Indiana. He was tried in a federal court, convicted, and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

James Bacik is a renowned Catholic theologian in Toledo. He has a doctorate from Oxford and has authored many books on Catholic theology. I met him soon after the 9/11 events and found him to be a sensitive and thoughtful person who did not preach superiority of his religion. It would be considered a heresy in most organized religions. His church, Corpus Christi University Parish, is unique that in addition to the murals of Catholic saints, there is a mural of Mahatma Gandhi.

In 2003, we were invited by the university of Toledo to participate in Catholic Muslim Dialogue where representatives of the two religions discuss certain aspects of their respective faiths. These dialogues are meant to underline common threads between the two religions.

I met Father Bacik over lunch a few weeks prior to the Dialogue to explore different themes that we could address. He said that traditionally the speakers turn the Dialogue into showcasing and boasting about their religion. He suggested that instead we consider looking inwardly and be critical of certain aspects of our religions.

Every religion is subject to interpretation and those interpretations often differ substantially. So, we discussed misinterpretations of certain passages in our sacred texts.

The dialogue was a great success. The following year we teamed up again and discussed heroes and saints in our mutual traditions.

Religion is a dynamic institution. For it to remain relevant, old interpretations must be re-examined. While the basics are fixed and unchangeable, there has always been room for interpretation according to prevailing times or Ijtehad.

The City of Toledo is unique in the sense that most religious groups get along fine with each other. If there are prejudiced people, and I am sure there are many, they keep their venomous hatred to themselves and don’t go about spewing it in public.

Part of the credit for religious harmony in Toledo goes to a visionary couple, Woody and Judy Trautman. In 2001, they formed the Multifaith Council in our part of the state that encompass all religions. The council promotes the common thread of humanity between different religions. An interesting fact is that Judy Trautman, while Christian, follows the Sufi traditions as taught in the west by Vilayat Inayat Khan, an Indian Sufi Muslim.

In most places in the world, religions live in splendid isolation from other religions. Mostly, they have little or no interaction with other religions on an ongoing basis. They are like the islands in a vast ocean. It is truer of religions that are in minority in countries that have only one dominant religion. It is incumbent upon the followers of the dominant religion to reach out and build bridges of understandings with the minority religions. If we have an ongoing dialogue among different faiths, we can overcome political, ethnic, and religious polarization.

It is always more useful to build bridges than destroy them.

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain is an emeritus professor of surgery and an emeritus professor of humanities at the University of Toledo, USA. His is also an op-ed columnist for the daily Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar. He may be reached at [email protected]